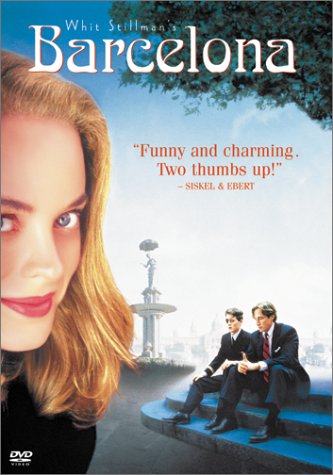

“The Last Days of Disco” is the final installment in Whit Stillman’s trilogy of films in the lives of terminally talkative young people. As with his earlier two films, “Metropolitan” and “Barcelona,” the world of the film is sadly lacking in role models and authority figures. Unlike the boys of Never Never Land, these characters are very clearly bent on becoming adults, even as they flail about rather piteously for some semblance of solid ground. More importantly, these films are in stark contrast to the more modern fantasy “The Breakfast Club.” This is not a film about self-discovery or self-actualization, but about coming-of-age in a more traditional sense: growing up, leaving childish things behind, grounding oneself in the received wisdom of one’s parents and one’s culture. The characters do not seek to come to terms with they were, but rather with who they ought to become.

|

| Directed by Whit Stillman, starring Kate Beckinsale and Chloe Sevigny Content warning: some nudity and scenes of sexuality, some language, some drug use |

Stillman's film is is deeply, even reflexively ironic; this trait is expressed not only in the screenplay, but even in the casting. Tom is played by Robert Sean Leonard, the charming actor who plays Neil Perry in “Dead Poet’s Society,” who sets up all the right expectations for us to look at him as Alice does: as a prospective match. Alice herself is played by Chloe Sevigny, very much against type considering the rest of her career. Charlotte is played by Kate Beckinsale, who had only a few years earlier played the eponymous lead in the BBC adaptation of “Emma,” a similarly manipulative but essentially good-natured lady who grows up over the course of that film. Then there are in-jokes, as Stillman marshals characters from previous films across the stage. Ted from “Barcelona” counsels Jimmy about jobs in Europe, and notes wryly that “Barcelona is beautiful, but in human terms it’s pretty cold” (echoing some of that film’s critics). Audrey from “Metropolitan” is seen from afar, rumored to be not only accomplished (“the youngest person ever to make editor”) but tremendously perceptive (Charlotte was interviewed by her, and worriedly comments that “she saw right through me.”) These are circles within circles, ironies embedded within, even if only apparent to a film critic.

Soon into the film, Alice is persuaded to rent a railroad apartment with Charlotte and another friend, Holly, despite the pair's obvious incompatibility. This turns out to have been a horrid idea, as there are only two bedrooms, and both of Alice’s roommates seem to be as horny as rabbits. Alice herself loses her virginity to the lawyer Tom shortly thereafter, consummating a years-long infatuation. She had let Charlotte’s cruel words fester, especially the ridicule that had been heaped on her chaste ideals and “cold” persona, the frigidity of a “kindergarten teacher” in a sexually liberated age. Tom loses his charm after treating her as a one-night stand, dismissing her to the morning “walk of shame,” casually noting that he had cheated on his current girlfriend by sleeping with Alice, and revealing that he’d given her both gonorrhea and herpes to boot. But in Stillman’s world even the most unsavory characters can still demonstrate insight, and Tom has both in spades: he reveals that he had been attracted to her precisely because of her purity, and had deplored the “slinky seductress” act she had used to land them both in bed.

This revelation leads Charlotte to confess a much earlier (and if such a thing be possible, much greater) sin: while they were roommates in college, Charlotte had seduced any boy who expressed an interest in Alice, so Alice would think herself unattractive and begin to regret her purity. This is a pivotal moment, not only for Alice’s character, but for our understanding of Charlotte. It is here that we realize that, despite her pretense of confidence (exulting over the crowded dance floor “We are in complete control”) Charlotte is deeply, almost pathologically insecure, and that she lashed out at Alice precisely because she acted as such a stark reminder of Charlotte’s own inadequacies. From this point forward, the film works at reclaiming romance and sexuality from the controlling grasp of 'sexual liberation' that Charlotte (and later Des) represent.

In the middle of the film, we are treated to a remarkably penetrating discussion between Alice and her competing love interests Josh and Des on the Disney film “Lady and the Tramp.” Alice notes that she had watched it with her niece and found it depressing. Charlotte is incredulous (“A children’s film about loveable dogs is depressing?”) but Josh agrees. He notes that Lady is an essentially vapid princess-figure, while the Tramp is a self-confessed chicken thief, a criminal. Josh does quite a intriguing bit of analysis: “The film programs young girls to be attracted to the bad element, so that fifteen years later, when that kind of boy does show up, their hormones will be racing and no one will understand why.” He continues, “The only sympathetic character is the Scotty dog, who genuinely cares about Lady” but is dismissed as obsolete.

Josh takes a breath, and Des pipes in: “But isn’t it clear that the moral of the story is that Tramp changed, that he gave up his chicken-thieving ways and becomes a part of this rather idyllic family with Lady in the end?” The conversation rages, but it’s clear from their vehemence that both men have more than puppies on their mind. Josh is making the case that he’s the best fit for Alice since he is already has a noble personality: “We can change our contexts but we can’t change ourselves.” Des is (rather desperately) working another angle: he admits he is a ‘bad boy’ right now, but implies that by Alice’s influence he might learn to become good.

By the penultimate scene, it’s clear who was right. Josh gets the girl, and Des flees the country when his boss is arrested. In the taxi to their airport, he states his intention to “turn over a new leaf in Spain” then asks aloud: “You know that line from Shakespeare, ‘To thine own self be true’? It’s premised on the idea that ‘thine own self’ is something good, being true to which is commendable. But what if ‘thine own self’ is not so good, what if it’s pretty bad? Wouldn’t be better not to be true to thine own self in that case?” He admits he’s “running like a rat” because that is who he is, but recognizes that it would be far better if he were not true to his nature. Contra the loveable misfits of “The Breakfast Club,” it is neither finding nor accepting who you are, but improving who you are through virtue, that leads to happiness. Whether in conveying the depths of human emotion and experience, reveling the subtleties of irony and language, or presenting insight into the very nature of things, "The Last Days of Disco" remains a truly magnificent film that I highly recommend.

One final note: "The Last Days of Disco" is not a film about plot or big events. The narrative is framed by events, not defined by them. Josh may be the A.D.A. responsible for investigating the disco club for money laundering and drugs, but the story remains on how that affects his friendship with Des and his pursuit of Alice's heart. Besides a brief moment where Josh finally gets to say "Book this clown!" in arresting the club's owner, the drug bust itself is largely relegated to the background. Nor is this a film about big characters or personalities. The final words of the film are giving to Des and Charlotte, talking about how their “big personalities” overshadow the more normal-sized personalities of Alice or Josh, or the “itsy-bitsy teeny-weeny yellow polka-dot bikini-sized personality” of Jimmy. This may be true – they were the most interesting characters depicted, and Stillman couldn't have sustained an entire film populated solely with people like Alice -- but it is not to their credit. Like Jane Austen in “Mansfield Park,” Whit Stillman contrasts a soft-spoken but virtuous heroine with a more effervescent but also amoral competitor, and there is no contest. Austen’s novel serves as an antidote to her other novels, which tend to present sparkling wit and vivacity as the best virtues in a person. The same applies here, as "The Last Days of Disco" is an antidote to the entire genre of romantic comedy. Love is not about a couple's ability to dominate the silver screen, but in their degree of virtue, which makes for far less compelling drama. Even so, is there any question that Alice will be happier than Charlotte, when all is said and done?